Love in an Elevator

A few days later I’m waiting for the elevator in the central elevator bay, which I usually avoid. I’m using the central bay because the west bay is not working today, which is—unfortunately—not unusual.

The central bay was built as part of the original hospital in the nineteen-forties. As you travel up, it feels like the elevators move by a series of connected rubber bands. You can feel variations in your speed and watch passengers grab the handrails, nervously glancing at one another. When your floor is reached, the elevator car will slow, stop, lower, and than raise a bit. The effect can be compared to motion of a Slinky as it finds its hanging point. They usually stop within a foot or two of the floor. Often not the floor you requested, but close enough that you only have to take the stairs up or down a single flight.

On each of the floors the elevator bay is equipped with phones so when you walk by the hall and hear the screaming of people trapped in between floors you can let elevator maintenance know. I have that phone number programmed into my cell phone. I also have a fair number of friends I made while trapped between floors.

The newer elevators in the west bay do not trap you (much) and don’t move with rubber band motion, but they’re frequently broken.

So I am at the central bay, waiting.

A smiling, thin, middle-aged black man joins me. He presses the up button, though it’s already lit, to announce that he—also—is waiting for the elevator. He then asks me if I am a doctor.

I’m looking at my shoes when he asks this, so in my field of vision I can see my white coat, my stethoscope, and the embroidering—cheap embroidering—of my coat that spells out the word ‘Doctor’ before my name begins.

He’s friendly enough and I haven’t been able to immediately glean his angle, so I just say yes.

‘Awesome job you have, man.’

Though awesome’s meaning is rather specific—either awe inspiring or excellent—it can be pronounced many ways, and the pronunciation very specifically communicates which meaning is intended. His meaning was clearly not the Bill & Ted variety of ‘great job with golf and cash and seeing naked chicks.’ His was of the church going variety with ‘vocation and mission and helping the afflicted.’

‘Sometimes,’ I said, a bit flatly but punctuated with a—hopefully—pleasant nod.

‘Well, I think it’s an awesome job,’ he said and began talking about why he thought so.

I pressed the call button again.

He kept talking when we got on the elevator.

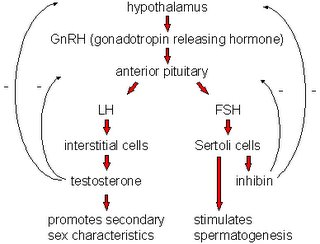

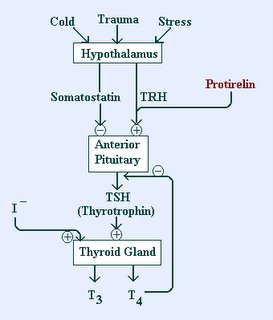

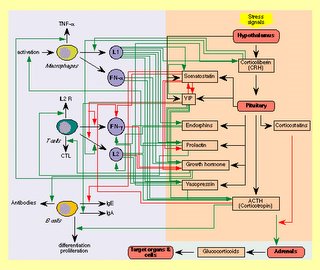

‘I have a friend who’s a doctor,’ he said, ‘and he says that when he sees the complexity of the human body, the hormones and the way they’re regulated, he says its clear we’re designed by an awesome God.’

I knew doctors like his friend in medical school. They were the kids who confused landscape design’s approximation of natural beauty with its reversal: natural beauty’s approximation of landscape design.

Granted, the simplified flow charts and regulatory pictogram that recall electrical schematics and circuit diagrams can be misleading. Illustrations that explain the way something works can be mistaken for the why something works.

Granted, the simplified flow charts and regulatory pictogram that recall electrical schematics and circuit diagrams can be misleading. Illustrations that explain the way something works can be mistaken for the why something works. These people revealed themselves with their confusion when the way and the why were at odds with each other, when elements had no obvious use, or no discernable why: the molecular equivalents of an appendix.

I don’t join the religious fervor of people who mock creationists. They often have less understanding of the history and details of evolution than a twelfth-century peasant understands the Holy Roman Empire yet rails against paganism.

I tried to make eye contact with him, to be friendly, but what I was really thinking was that his friend was probably loved by his patients—because, contrary to popular opinion, you don’t have to be a great thinker or possess great understanding to be a good doctor: For the most part you can get by with memorized algorithms and lists. That kind of doctor is loved by his patients because he refers everything out to specialists. The patients think they are special, why else would they go to a specialist? But that kind of doctor doesn’t truely understand what he’s observing.

To be a great doctor you have to kill your own awe. You must be willing to defy god, to tinker with his creation, to alter and change the way the human body functions to keep it alive until it can resume homeostasis.

To be a great doctor you have to kill your own awe. You must be willing to defy god, to tinker with his creation, to alter and change the way the human body functions to keep it alive until it can resume homeostasis.I am not awed by man’s body. There is no dread in my soul. When a patient is dying before me, he’s a mathematical equation that must be solved, a brain teaser, an Encyclopedia Brown Mystery whose clue needs to be discerned. I have no time or stomach for awe and wonder.

People wonder why doctors think they’re gods; I can explain it quite easily. Place you fingers on a cold, pulseless wrist. Say words that serve as an incantation that send women in white scurrying to administer agents of your choosing. Feel the pulse return to the wrist. Watch the eyes open.

It’s a simple parlor trick.

But go out and talk to the brain teaser’s daughter, the equation’s wife, the mystery story’s mother. You’ll have to avoid their eyes. Their eyes are full of the awe and wonder and dread that you have tried to kill. If you were in awe, if you felt the wonder of what you were doing, you would crumble. You would not be able to function in those crucial moments. And their watering eyes praise you. Their hands clasp around yours in gratitude. They tremble as they give you thanks.

You then—as I now, in the elevator—won’t know what to do with such praise.

The smiling, thin, middle-aged black man in the elevator has almost reached his floor. It has stopped just shy of it and, after I help him step the eighteen inches up, he turns to me and says, ‘God loves you.’

‘Yes,’ I say, pressing the door close button, ‘I’m aware.’

1 Comments:

3/02/2006

Unknown writes:

Unknown writes:

Encyclopedia Brown - have not thought of those books in years...

Post a Comment

Home